Building a reverse image search engine at EBTH

We built a reverse image search engine that looks up similar items sold by Everything But The House in the past, leveraging deep neural networks built on large image corpuses. Here’s how we went about finding the solution and implementing it.

Motivation

Items sold at EBTH are one-of-a-kind, but it is quite possible that we sold similar items in the past. Identifying such instances based on a simple photograph early in the process helps us in reducing effort involved in cataloguing and attribution and also in estimating an expected price. Down the road, it could be game changing tool for buyers to search by images from their phone instead of typing in a description. It could also help potential sellers look up the expected value of their item by looking at similar items previously sold at EBTH. The stakes are huge.

Challenges

- How do you compare two images for similarity?

- How do you compare an image with a million others?

- How do you do it in less than a second?

Some Background

For all the advances in computer science over the past 5 decades, the ability of a computer to understand language (think google translate 10 years ago), speech (early Siri) and particularly images was quite limited until very recently. While a computer could easily solve complex mathematical equations, a toddler is better off than a computer at identifying its mother at any angle, setting or background. Even in early 2000s, similarity comparison between images typically used rudimentary measures like histograms, color profiles, frequency domain representation etc., which are quite limited in their effectiveness unless the images are near identical. Post 2012 a paradigm shift happened in the form of Deep Learning (short for neural network architectures with more than one layer of ‘neurons’, hence deep). Deep neural networks are black boxes that process an input (of numbers) through numerous layers of computation to arrive at an output (of number/numbers). With enough training data (input:output pairs) it can figure out the relation between the input and output even if the relationship is very complex. It is important to point out that neural networks treat the input and output purely as numbers and do not have a need to ‘understand’ what the input/output mean in real life. Therefore they can applied in variety of domains like genetics, credit scoring, speech recognition etc. by even novices who have no subject matter expertise.

The Solution

How do you compare two images for similarity?

Each year, the group behind ImageNet, a large open-source database of hand-annotated images, conduct the ImageNet Visual Recognition Challenge where algorithms are evaluated based on accuracy of object detection. These algorithms accept the pixels of an image as the input and spit out the likelihood of a particular object being in the image as the output. Over the years, the winners have open sourced their algorithms and architectures to the broader community. While the primary purpose of the algorithms is to classify images into predefined set of categories, the outputs from the intermediate layers of the neural network can be considered as ‘features’ of the image. These ‘features’ are essentially ‘fingerprints’ of the image and they can be compared with fingerprints of other images. For its simplicity and ease of use, we used the VGG model, which won the ImageNet challenge in 2014. In particular, the outputs from the penultimate layer of VGG (a vector of length 25088 for images of the dimension 224 X 224) are extracted for the two images and their cosine distance is used as the measure of similarity. Step by step explanation in this blog.

How do you compare an images with a million others?

Generating features for two images using VGG model and calculating cosine similarity is pretty fast and takes about a couple hundred milliseconds on a GPU instance (AWS p2.x large). But generating similarity scores for a million pairs on the fly even if the image features are pre-extracted and stored has a latency in the order of minutes. While the similarity results are quite convincing, the practical usage of a system with query time running into minutes is very limited. To speed up the process, we explored several options like elastic search for vectors, local sensitive hashing, DIMSUM (used by Twitter) and dimensionality reduction algorithms like PCA, the results were either unsatisfactory or hard to implement. Which brings us to the final challenge.

How do you do a million comparisons in less than a second?

Thanks to a blog on benchmarking nearest neighbor algorithms, we stumbled upon ANNOY, a library that fetches (approximate) nearest neighbors, which is blazing fast compared to our earlier approaches. The library indexes the vectors as a hierarchical tree where each node is a plane cuts the space into two subspaces essentially forming smaller and smaller buckets of subspaces which makes querying through the tree very fast (more on methodology here).

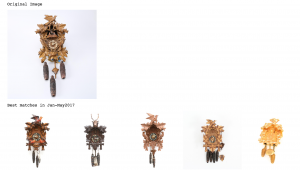

Results

The results have been quite impressive. Here are a few examples.

We will continue to optimize the process to improve accuracy and reduce lookup time.

This blogpost was first published on EBTH’s Engineering Blog in Feb 2018